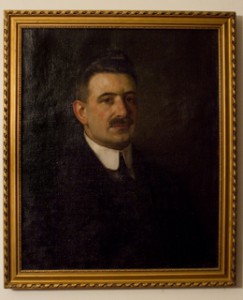

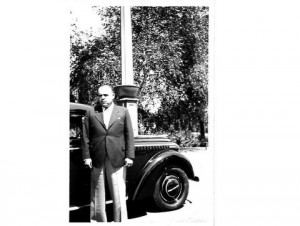

He virtually had no personal memories of his father – this is probably the only one. A barely visited grave in the cemetery with a small marble plate in gold print: Dad. He was not yet five when his father died.

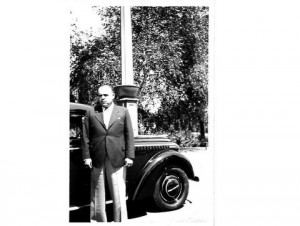

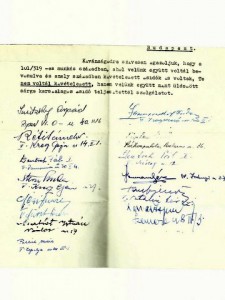

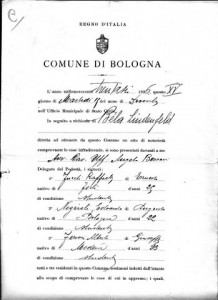

He was already a father himself when he started to look through the old photographs and yellowing documents: few memories of a life without extraordinary qualities. His parents lived the life of well-off bourgeoisie, his father a merchant. They lived in a fine apartment and they had their own car, a dark blue Opel Olimpia. He knew from his mother that Dad was addicted to playing cards, a small fortune was claimed by chemin de fer. Dad followed religion, he was a major contributor and alderman of the Csaky Synagogue.

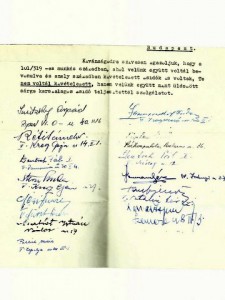

With the emerging Jewish legislation, opportunities became scarce. A loyal aryan employee registered Dad as a sales agent in his own shop. Stricter regulations still forced him to leave here too. Forced labor, escape and hiding followed. His health deteriorated – history did not serve well his weakened heart. Then, after the war, a few free years, all too short. Then communist nationalization: they took everything he had. Some odd jobs of grace, blue-collar work, deprivation, end-game. It was around this time that he was walking with Dad on the street one winter and someone came up to them asking for change to buy food. Dad gave him some money and when the stranger moved on, he told his son: “you see, he had a better coat than mine.”

A few months later the first warm sunshine of spring took them to Margitsziget with Mom, Dad and Granny. It was there that Dad collapsed and died in a second – today he only remembers the crying and screaming at the scene.